Table of Contents

Styles of Japanese Painting

Haiga

Haiga

Poetry painting. Abbreviated playful painting, matching equally abbreviated haiku poems. A style often practiced by amateurs. Please look at the Toro (Lantern) Scroll here:

Kanô

This became what was termed as the official painting style of the Japense goverment. Popular in Edo as well as in Kyoto. Kano was based on Chinese styles from the Muromachi period.

Painting in the broken-ink technique (hoboku) and adding colour to traditional subjects. Saying that , sumei style (ink paintings) Kano was also popular.

Kishi

Nagasaki, KanÙ and Maruyama-ShijÙ painting styles with a very recognised brush stroke.

Maruyama

Maruyama ’kyo, emphasises the artists study of and response to nature (Shaseiga).

Muromachi

The Muromachi school originated under the influence of the Chinese Sung and Yang dynasty paintings that were brought to Japan during the later Sung Dynasty with many other art subject mater like Puntsai (Bonsai) and silk clothing and material and later into the 14th century by Zen monks who could make a small income from painting.

Nagasaki-e

Is a painting style influenced by the Chinese (and the Dutch) at Nagasaki.

Nanga

Also known as Bunjinga, a literati painting style worshipping things Chinese, includes painting and poetry, and prizing amateur status.

Nihonga

This is the ‘native’ Japanese style developed in the Meiji period by teachers at the newly established academies. Mixed traditional Japanese styles mixed with Western techniques. Marked differences apparent between the Tokyo and Kyoto based Nihonga artists.

Rimpa

A decorative painting style.

Shijô

A style that is closely related to Maruyama painting, but a little more poetic, less restricted and with a more innovative brush stroke.

Tosa

This is also known as the Yamato-e style. Official court painting style, specialised in Japanese subjects. There was a general revival of this style in the beginning of the 19th century. Colourful miniature like brushwork with a long tradition of panting hand scrolls (emaki). Known widely as Ukiyo-e which are the paintings of urban life. These have a particular emphasis on the pleasures of the ‘floating world’: prostitution, fashion, kabuki, sumo and other recreations.Japan was called the floating world.

Zenga

Although these can be paintings they are more often calligraphies drawn by Zen priests and laymen

Japanese painting, western influences and how changes in fashion have affected scroll art

Sansuiga (landscape painting) is a genre of the picture which developed in China through the early Sung Dynasty and when that arrived in the 19th Century started to be more representative of traditional scenic views. Often hung in homes at certain times of the year, the Landscape painting of China usually had descriptions or poems about the view. However when the art developed in Japan the many views of Japan developed earlier and became extremely popular as woodblock prints which were an inexpensive means of printing that allowed the ordinary person to have some art representation of views of Japan in their own homes. One centre of Woodblock printing was in Kyoto which was a popular tourist destination even for the Japanese well before the west arrived with Commander Perrys Black ships in 1852 and 1854.

Sansuiga (landscape painting) is a genre of the picture which developed in China through the early Sung Dynasty and when that arrived in the 19th Century started to be more representative of traditional scenic views. Often hung in homes at certain times of the year, the Landscape painting of China usually had descriptions or poems about the view. However when the art developed in Japan the many views of Japan developed earlier and became extremely popular as woodblock prints which were an inexpensive means of printing that allowed the ordinary person to have some art representation of views of Japan in their own homes. One centre of Woodblock printing was in Kyoto which was a popular tourist destination even for the Japanese well before the west arrived with Commander Perrys Black ships in 1852 and 1854.

Buying a print or a book of prints would be an excellent way for a visitor to take back home a reminder of a wonderful trip. Even today, the Japanese love to travel and instead of buying prints simply take pictures with their cameras of everything and anything that moves or stands still. Art collection and appreciation was no longer one of the pursuits of the ruling classes and Samurai leaders. In the 19th century the art of the great woodblock painters came to the fore in Europe and heralded the inspiration for the growth of what became ‘Impressionism’.

Although Japanese art in the western style did not fully open up until a little later in the late 19th century it opened with an almost evangelical move from the population that could afford to gratify their desire for western fashions and ideas. An explosion of a kind of freedom meant that many of the old trades and arts were put to one side in favour of more western ideas. Fortunately the traditional arts were kept by a few and these returned gradually during the early part of the 20th century and it s from this period that many fine scrolls were created for the emerging Western export markets. One of these markets was for the popular oriental type goods for Western homes in Europe and America. The Dutch East India Company through their trade compound in Nagasaki had been exporting these kinds of goods from Japan for almost 200 years and they were quite expensive but now the market was wide open and prices became affordable for some quite wonderful artwork. One modern example of this story of the Japanese coming to terns with the west was in Stephen Sondheim’s opera, Pacific Overtures(1976) which I had worked as fight director for the Japanese Sword scenes in this Opera in 1987 at English National Opera. One song stands out for me and that was ‘A Bowler Hat’ which neatly encapsulates the show’s theme, as a Samurai gradually sells out to the Westerners. This was , for me, a masterpiece by Sondheim to crystallise the change that many Japanese went through quite willingly. Not all but enough to drive the way forward.

The word san means yama (mountains), sui means mizu (river), ga means a picture. There is the work which aimed at reproduction of real scenery, but there is also “created scenery” “image scenery” which constituted scenery elements such as the mountains / trees / rocks / rivers by realism again. Artistic licence. Taking an existing scene and enhancing it in a way that would attract the buyer to place this on the wall of their home. but more than this it was a representation of a spiritual place. Mountains where spirits reigned, hidden valleys full of myths and legends.

The word san means yama (mountains), sui means mizu (river), ga means a picture. There is the work which aimed at reproduction of real scenery, but there is also “created scenery” “image scenery” which constituted scenery elements such as the mountains / trees / rocks / rivers by realism again. Artistic licence. Taking an existing scene and enhancing it in a way that would attract the buyer to place this on the wall of their home. but more than this it was a representation of a spiritual place. Mountains where spirits reigned, hidden valleys full of myths and legends.

The art of Japan has a powerful Chinese influence. There was originally no word for simply “Fukeiga (Fukei=scenery-ga=Picture)”. The picture which assumed a representation of natural scenery was simply called “a landscape painting”. Originally “Sansuiga (landscape painting)” began as spiritual world expression to be based on a legendary Chinese hermit with miraculous powers of thought.. On the other hand, the Meiji era began, and the words of “scenery” became established with the full-scale introduction of Western paintings. In “Fukeiga (Scenery)”,the eyes of the naturalism or realism assumed a form that was different from a conventional “Sansuiga (landscape painting)” the basis of the landscape scenery style of painting were incorporated, and natural reproduction by a rational technique was aimed at the subject matter of the art work.. However, while taking in such techniques, some of the traditional Japanese landscape painting became based on a sense of beauty of the subject matter rather than the actual image itself. So floating clouds and misty forests, cool waterfalls and scented glades became the holy grail of the Japanese Landscape painter of scrolls.. The scroll therefore does not have to be as detailed as a western landscape but rather an impression, a feeling of what the viewer is looking at. A successful landscape scroll delivers this. The waterfall should make you feel cool ad the forest should suggest the smell of damp leaves and birdsong and the mountain should make you feel that you become part of the birds flying below the cold peaks. Viewing a Japanese landscape scroll relies on the viewer relaxing and becoming one with the scene.

The art of Japan has a powerful Chinese influence. There was originally no word for simply “Fukeiga (Fukei=scenery-ga=Picture)”. The picture which assumed a representation of natural scenery was simply called “a landscape painting”. Originally “Sansuiga (landscape painting)” began as spiritual world expression to be based on a legendary Chinese hermit with miraculous powers of thought.. On the other hand, the Meiji era began, and the words of “scenery” became established with the full-scale introduction of Western paintings. In “Fukeiga (Scenery)”,the eyes of the naturalism or realism assumed a form that was different from a conventional “Sansuiga (landscape painting)” the basis of the landscape scenery style of painting were incorporated, and natural reproduction by a rational technique was aimed at the subject matter of the art work.. However, while taking in such techniques, some of the traditional Japanese landscape painting became based on a sense of beauty of the subject matter rather than the actual image itself. So floating clouds and misty forests, cool waterfalls and scented glades became the holy grail of the Japanese Landscape painter of scrolls.. The scroll therefore does not have to be as detailed as a western landscape but rather an impression, a feeling of what the viewer is looking at. A successful landscape scroll delivers this. The waterfall should make you feel cool ad the forest should suggest the smell of damp leaves and birdsong and the mountain should make you feel that you become part of the birds flying below the cold peaks. Viewing a Japanese landscape scroll relies on the viewer relaxing and becoming one with the scene.

Figurative art

Figurative art has remained largely the same. Modern examples from the early 20th century until the mid 1960’s relied on traditional woodblock prints of detailed costume pink faces with lined eyes and facial features and little or some background. Quite beautiful, these rarer paintings were all about the detail. This detail is shown in the Takasago and Shogun paintings. Originally these were quite simple with some detail. Around the 18th century they started to change and developed into the art from of the woodblock in the mid 19th century. Well why change something that does not need to be changed. Later artists utilized the stylistic approach of the 1850’s to the scrolls of the 1950’s and these were well appreciated by both Japanese and foreign buyers. In some cases, the painting was so well thought of that the artists even made the matching box and inscribed lengthy detail on the inside and the back of the box.

Pine of Takasago and Jo and UBA

It represents a scene from a Noh play based on the subject of the Eternal Couple from the Legend of Takasago. Jo and Uba were supposed to have fallen in love when young, and after living to a very old age their spirits came to abide in pine trees,one on the beach at Takasago in Harima, and the other at Sumiyoshi in Sesshu near Osaka. Their spirits returned on moonlit nights in human form with rakesto continue their work of clearing the pine needles on Takasago Beach.

It represents a scene from a Noh play based on the subject of the Eternal Couple from the Legend of Takasago. Jo and Uba were supposed to have fallen in love when young, and after living to a very old age their spirits came to abide in pine trees,one on the beach at Takasago in Harima, and the other at Sumiyoshi in Sesshu near Osaka. Their spirits returned on moonlit nights in human form with rakesto continue their work of clearing the pine needles on Takasago Beach.

Jo and Uba are therefore the Gods of Marriage.

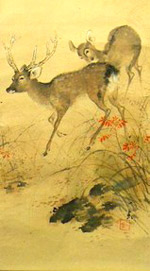

A word may be said also regarding the curious associations of animals and plants, to which some symbolism originally attached, but which apparently have been repeated very much like the copies of Chinese pictures, out of respect for tradition only. Amongst others will be noted the Quail and Millet, Peacock and Peony, Shishi and Peony, Swallow and Willow, Tiger and Bamboo, Plum Blossom and Moon, Chidori and Waves, Deer and Maple, Boar and Lespedeza, most of which are of frequent occurrence. The Snake is also often shown coiled around a Tortoise sometimes with jewel (Tamo), reminiscent of the Snake and Egg Myth and then associated with Bishamon.

CRANE, Emblem of longevity, attribute of Seiobo, Jurojin, Fukuro ~ . Kujiu, Tobusako, Jofuku, Wasobioye, Oshikio, Yoritomo, Toyu, Jo and UBA, Kohaku. Kaxgai Sennin ; Isetsu ; Kodokwa ; Teireii. Crane, Conch Shell which is the emblem of the Yamabushi PINE (Matsu). Emblem of strength, endurance, longevity, because it is believed that its sap turns into amber after a thousand years; the “Sea Pine” is a fossilised wood, almost translucent, pieces of which were much prized as netsuke. PINE, red and black, emblematic of happy marriage. TORTOISE. (freely crossed meaning with Turtle) Emblem of Longevity

Birds and Animals

Birds and animals also remained largely the same as before. Birds are usually depicted in much greater detail and auspicious birds suc as Eagles usually have great detail while the crane in both Japan and China holds great significance. Crane paintings seem to have less detail and are more about shape, design and story. Two cranes are depicted together to suggest marriage and are included in mythology paintings such as Takasago

Birds and animals also remained largely the same as before. Birds are usually depicted in much greater detail and auspicious birds suc as Eagles usually have great detail while the crane in both Japan and China holds great significance. Crane paintings seem to have less detail and are more about shape, design and story. Two cranes are depicted together to suggest marriage and are included in mythology paintings such as Takasago

Animals

Tsuru: The Japanese Crane

Many classical Japanese folktales and paintings have appeared, featuring the beauty of tsuru in their long necks and legs. They are winter migratory birds, that fly to Japan in October from Siberia and Mongolia, returning the following year in March. In Japan they are valued especially as animals symbolizing long life and are often used for festive designs and decorations. Senbazuru (One Thousand Cranes) of origami (folded paper) are sent to the sick to pray for recovery from illness and for long life. Cranes are also birds that mate for life and as this is such an auspicious behaviour, giving such a scroll to a newly married couple or for a wedding anniversary is a profound and meaningful thing to do.

Paintings on scrolls of animals usually reflect legends , mythology or rarely actual animals.

Paintings on scrolls of animals usually reflect legends , mythology or rarely actual animals.

In some scrolls Yamabushi Tengu, the long nose Goblin, directs the forest monkeys against the peaceful Tanuki. Monkeys were either thought to be deities, disease infested forest pests or in Chinese Mythology, very high up in the Deity pecking order, The Monkey King is a traditional character from Chinese Opera. Many of these myths found their way into Japan and these were adapted and changed along the way.

The Fox Priest: The Fox who became a Priest

The traditional Japanese fable tells of an old fox who has grown tired of being hunted. He disguises himself as an elderly priest named Hakuzosu, known for his love of foxes. The fox visits a nephew of the priest who is a hunter and tells him of the many virtues of foxes, as well as of the punishments that come to men who take life. Satisfied that he has accomplished his mission, he leaves to return home. On the way, however, he begins to turn back to his true form and loses the capacities of foresight and reason. A baited trap before him is an irresistible temptation and he is caught. Yoshitoshi shows the disguised priest walking among tangled weeds in the moonlight. As he glances over his shoulder, we are made aware of his true nature by the change which has already occurred in his face…The fable may be: People may not be what you think they are, but always look on the other side of every story

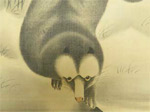

Tanuki (狸 or タヌキ?) is the Japanese word for the Japanese raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus). They have been part of Japanese folklore since ancient times. The legendary tanuki is reputed to be mischievous and jolly, a master of disguise and shape shifting, but somewhat gullible and absent-minded.

Tanuki is often mistakenly translated as raccoon or badger. Statues of tanuki can be found outside many Japanese temples and restaurants, especially noodle shops. These statues often wear big, cone-shaped hats and carry bottles of sake in one hand, and a promissory note or empty purse in the other hand. Tanuki statues always have large bellies. The statues also usually show humorously large testicles, typically hanging down to the floor or ground, although this feature is sometimes omitted in contemporary sculpture.

Tanuki is often mistakenly translated as raccoon or badger. Statues of tanuki can be found outside many Japanese temples and restaurants, especially noodle shops. These statues often wear big, cone-shaped hats and carry bottles of sake in one hand, and a promissory note or empty purse in the other hand. Tanuki statues always have large bellies. The statues also usually show humorously large testicles, typically hanging down to the floor or ground, although this feature is sometimes omitted in contemporary sculpture.

November 8 is the date for the Tanuki holiday because the emperor made his famous visit in November and because the tanuki has eight special traits that bring good fortune. The eight traits are: (1) a bamboo hat that protects against trouble, (2) big eyes to perceive the environment and help make good decisions, (3) a sake bottle that represents virtue, (4) a big tail that provides steadiness and strength until success is achieved, (5) over-sized testicles that symbolize financial luck, (6) a promissory note that represents trust, (7) a big belly that symbolizes bold decisiveness, and (8) a friendly smile.

The comical image of the tanuki is thought to have developed during the Kamakura era. The actual wild tanuki has unusually large testicles, a feature that has inspired humorous exaggeration in artistic depictions of the creature. Tanuki may be shown with their testicles flung over their backs like travellers’ packs, or using them as drums. As tanuki are also typically depicted as having large bellies, they may be depicted as drumming on their bellies instead of their testicles — particularly in contemporary art.

The comical image of the tanuki is thought to have developed during the Kamakura era. The actual wild tanuki has unusually large testicles, a feature that has inspired humorous exaggeration in artistic depictions of the creature. Tanuki may be shown with their testicles flung over their backs like travellers’ packs, or using them as drums. As tanuki are also typically depicted as having large bellies, they may be depicted as drumming on their bellies instead of their testicles — particularly in contemporary art.

During the Kamakura and Muromachi eras, some stories began to include more sinister tanuki. The Otogizoshi story of “Kachi-kachi Yama” features a tanuki that clubs an old lady to death and serves her to her unknowing husband as “old lady soup,” an ironic twist on the folkloric recipe known as “tanuki soup.” Other stories report tanuki as being harmless and productive members of society. Several shrines have stories of past priests who were tanuki in disguise.

Shapeshifting tanuki are sometimes believed to be tsukumogami, a transformation of the souls of household goods that were used for one hundred years or more.

Shapeshifting tanuki are sometimes believed to be tsukumogami, a transformation of the souls of household goods that were used for one hundred years or more.

A popular tale known as Bunbuku chagama is about a tanuki who fooled a monk by transforming into a tea-kettle. Another is about a tanuki who tricked a hunter by disguising his arms as tree boughs, until he spread both arms at the same time and fell off the tree. Tanuki are said to cheat merchants with leaves they have magically disguised as paper money. Some stories describe tanuki as using leaves as part of their own shape-shifting magic.

In metalworking, tanuki skins were often used for thinning gold. As a result, tanuki became associated with precious metals and metalwork. Small tanuki statues were marketed as front yard decoration and good luck charm for bringing in prosperity. Also, this is why tanuki is described as having large kintama (金玉 lit. gold ball, means a testicle in Japanese slang).

In metalworking, tanuki skins were often used for thinning gold. As a result, tanuki became associated with precious metals and metalwork. Small tanuki statues were marketed as front yard decoration and good luck charm for bringing in prosperity. Also, this is why tanuki is described as having large kintama (金玉 lit. gold ball, means a testicle in Japanese slang).

A kakemono (掛物?, “hanging”), more commonly referred to as a kakejiku (掛軸?, “hung scroll”), is a Japanese scroll painting or calligraphy mounted usually with silk fabric edges on a flexible backing, so that it can be rolled for storage.

As opposed to makimono, which are meant to be unrolled laterally on a flat surface, a kakemono is intended to be hung against a wall as part of the interior decoration of a room. It is traditionally displayed in the tokonoma alcove of a room especially designed for the display of prized objects. When displayed in a chashitsu, or teahouse for the traditional tea ceremony, the choice of the kakemono and its complementary flower arrangement help set the spiritual mood of the ceremony. Often the kakemonoused for this will bear calligraphy of a Zen phrase in the hand of a distinguished Zen master.

As opposed to makimono, which are meant to be unrolled laterally on a flat surface, a kakemono is intended to be hung against a wall as part of the interior decoration of a room. It is traditionally displayed in the tokonoma alcove of a room especially designed for the display of prized objects. When displayed in a chashitsu, or teahouse for the traditional tea ceremony, the choice of the kakemono and its complementary flower arrangement help set the spiritual mood of the ceremony. Often the kakemonoused for this will bear calligraphy of a Zen phrase in the hand of a distinguished Zen master.

In contrast to byōbu (folding screen) or shohekiga (wall paintings), kakemono can be easily and quickly changed to match the season or occasion.

The kakemono was introduced to Japan during the Heian period, primarily for displaying Buddhist images for religious veneration, or as a vehicle to display calligraphy or poetry. From the Muromachi period,landscapes, flower and bird paintings, portraiture, and poetry became the favorite themes.

The kakemono was introduced to Japan during the Heian period, primarily for displaying Buddhist images for religious veneration, or as a vehicle to display calligraphy or poetry. From the Muromachi period,landscapes, flower and bird paintings, portraiture, and poetry became the favorite themes.

If the width is shorter than the height, it is called a vertical work (竪物 tatemono or Standing Scroll (立軸tatejiku)); if the width is longer than the height, it is called a horizontal work (横物yokomono or horizontal scroll (横軸 yokojiku).

The “Maruhyousou” style of kakejiku has four distinct named sections. The top section is called the “ten” heaven. The bottom is the “chi” earth with the “hashira” pillars supporting the heaven and earth on the sides. The maruhyousou style, (not pictured above) also contains a section of “ichimonji” made from “kinran” gold thread.On observation, the Ten is longer than the Chi. This is due to the fact that in the past, Kakemono were viewed from a kneeling (seiza) position and provided perspective to the “Honshi” main work. This tradition carries on to modern times.

There is a cylindrical rod called jikugi (軸木) at the bottom, which becomes the axis or center of the rolled scroll. The end knobs on this rod are in themselves called jiku, and are used as grasps when rolling and unrolling the scroll. Other parts of the scroll include the “jikubo” referenced above as the jikugi. The top half moon shaped wood rod is named the “hassou” to which the “kan” or metal loops are inserted in order to tie the “kakehimo” hanging thread. Attached to the jikubo are the “jikusaki”, the term used for the end knobs, which can be inexpensive and made of plastic or relatively decorative pieces made of ceramic or lacquered wood. Additional decorative wood or ceramic pieces are called “fuchin” and come with multicolored tassels. The variation in the kakehimo, jikusaki and fuchin make each scroll more original and unique.